This is one of the best historical fiction novels I've read all year. Told in first person, it is the purported memoir of Christina Olson, from the painting *Christina's World* by Andrew Wyeth. The narrative shifts back and forth between Christina's early life (late 1800s through WWI) and her later life, after Wyeth appears and takes up unofficial residence at the small, rather hardscrabble farm in Maine that Christina shares with her brother Al. Exploring themes of loss and resilience, betrayal and loyalty within a family, and the relationships among art and labor and intimacy, this book is an immersive, nuanced reflection on a woman's life.Kline reflects in the afterword that she spent years sitting in front of the painting, researching, visiting Maine, speaking with people who knew Christina Olson and those in her life, and it shows in the tightness of the story, the clarity of the images, and the distinct voices of the characters. (IMHO, this is Kline's best novel.) Highly recommend.

Wednesday, November 30, 2022

Christina Baker Kline, A PIECE OF THE WORLD

This is one of the best historical fiction novels I've read all year. Told in first person, it is the purported memoir of Christina Olson, from the painting *Christina's World* by Andrew Wyeth. The narrative shifts back and forth between Christina's early life (late 1800s through WWI) and her later life, after Wyeth appears and takes up unofficial residence at the small, rather hardscrabble farm in Maine that Christina shares with her brother Al. Exploring themes of loss and resilience, betrayal and loyalty within a family, and the relationships among art and labor and intimacy, this book is an immersive, nuanced reflection on a woman's life.Kline reflects in the afterword that she spent years sitting in front of the painting, researching, visiting Maine, speaking with people who knew Christina Olson and those in her life, and it shows in the tightness of the story, the clarity of the images, and the distinct voices of the characters. (IMHO, this is Kline's best novel.) Highly recommend.

Tuesday, June 7, 2022

Nina de Gramont, THE CHRISTIE AFFAIR

Set in 1925, the novel is told mostly in first person by Miss Nan O'Dea, mistress to Agatha Christie's husband Archie. Nan's voice just sings, for it is intense without being overwrought (as, alas, some historical novels are), delicate and blunt by turns, and profoundly truthful. Nan's account is spliced with chapters in third person, focalized through Agatha, whose 11-day vanishing act after her husband declares he is leaving her is the impetus for the book. We come to sympathize deeply with both women. Immersive and beautifully written, with sentences that verge on poetry. Highly recommend.

Saturday, February 19, 2022

Charles Finch, AN EXTRAVAGANT DEATH

As always with Finch’s Victorian mysteries, this is an engaging and entertaining read, with the charming, urbane detective Charles Lenox, now middle-aged and married to Lady Jane and with two children, and with a narrator who delivers wry observations that make me chuckle inwardly as I read.

The book begins in London 1878 (a period I know and love). In the aftermath of a fictionalized version of the (true) corruption scandal that shook up Scotland Yard, Lenox’s potential presence at the trial is awkward, and PM Disraeli sends him off to America on a diplomatic mission. However, once in America, Lenox is waylaid by a case of murder, which takes him to Newport, where a young woman’s corpse has been found on the beach below the famous Cliff Walk. For those who are watching Julian Fellowes’s THE GILDED AGE, you will find some of the characters here, most notably Mrs. Astor who throws the ball that occurs toward the end of this book.

One thing I love about the book is that Finch knows the period so well that the details that immerse us in this other world are feathered in organically, and I always learn something new. For example, the word “backlog” comes from the “back log” in a fireplace. Shrapnel—gunshot loaded inside hollow cannonballs—was created in 1784 by a lieutenant named Henry Shrapnel. There was a tavern in Greenwich Village where officers used to meet during the Civil War, with spies, “called the Old Grapevine” (hence the phrase, heard it through the grapevine). I always enjoy those tidbits, like a raisin in a scone.

I also love the nimble, allusive language that captures nuances and small moments. Quoted passages are never as good out of context – but here are a few, just to give those readers unacquainted with Finch a sense for his prose. As the third one suggests, Finch has some of Austen’s tendency toward humorous understatement and shrewd observation of character.

“For the next two days London was layered in a fog so dense that according to the papers now fewer than eight men fell into the river from the West India Docks. All of them had been fished out quickly, fortunately, and none worse off than a glass of rum would cure, but as the papers said—still! A pretty pass things had come to, when men and women couldn’t walk the streets of the capital without the prospect of barging straight into a lamppost.”

Regarding Delmonico’s in NYC: “Lenox might have queried the wisdom of police commissioners meeting in the same place as the criminals—but it fit in with New York, where everything seemed to happen inches from everything else.”

“Most single young gentlemen of large fortune he had known were drunk with their own high valuation of themselves, knowing it was held by others too; few Mr. Bingleys to be found anywhere, at any time.”

“… the article’s writer … was identified as J. Gossip Gadabout, a name which Lenox, with his years of practice in detection, strongly suspected of being a pseudonym.”

If you haven’t read the previous novels in the series, you can begin here; it works as a standalone.

Monday, February 7, 2022

Charlotte McConaghy, MIGRATIONS

Some readers had difficulty with how much this book jumped around from present to various pasts, but that didn't bother me so much. The author wrote in a way that made me trust that they would all fold together by the end.

But [*spoilers ahead*] I found myself a bit overwhelmed by all the grief and past trauma. I know it's what people write now ... it has become de rigueur for everyone from writers of literary fiction to Ted Lasso to uncover a backstory element such as an abusive father or a lost mother or a near death experience in their childhood. I find myself growing restless in the face of it, especially when it isn't necessary to generate narrative power. In this book, Franny experiences at least 8 different serious traumas [*spoiler alert*] that we find out belatedly, as they take place before the timeframe of the story: childhood poverty and deprivation, a feeling of not belonging, a mother who abandons her, a father in jail, the death of her child, the death of her beloved husband, the death of two other people, and jail time and the violence that entails.

Early on she explains, "one way or another, when I reach Antarctica and my migration is finished, I have decided to die" and though it feels a bit melodramatic on page 27, by the end of the book I feel like her redemption and the happyish ending almost seems as unlikely as all the trauma that caused her original suicidal wish.

This isn't to say that horrifying things don't happen to people, and sometimes they happen in multiples. I wrote my PhD diss on Victorian railway disasters because I was interested in how the experiential category of "trauma" (and PTSD) evolved out of early medical and legal discourse used to address the bizarre and often belated injuries suffered by train wreck victims. The subject fascinates me, and I think we need to continue to examine trauma and its aftereffects on the psyche and the body (as well as to resist the tendency to think of every grief as traumatic; the term loses its usefulness). I just felt like I was getting a bit hammered by it in this novel. Other people will feel differently, I'm sure. This said, I would definitely recommend this book. There's so much good here -- it's eloquent and poetic, a book that made me think about our fragile world, and a page-turner all at once.

Thursday, February 3, 2022

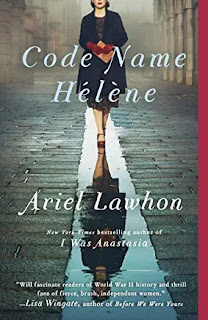

Ariel Lawhon, CODE NAME HELENE

4.5.

I have to confess, I have felt a bit burned out on WWII books, with many books in recent years featuring women as spies, coders, secretaries, land girls, resistance fighters, parachuters, etc. But I appreciated this one. Like THE WOLVES AT THE DOOR, by Judith L. Pearson, about the (historical, real-life) American spy Virginia Hall, this book, based upon the Australian Nancy Wake, a newspaper free-lance writer turned resistance leader, has the feel of the real.

The book is well-written, well-researched, and engaging, and my gripes are small: at times, I found the language a bit fraught, loading up the emotions somewhat improbably and with references that feel somewhat forced. (From page 87: Frank opens his mouth and I know where he's going so I stick my finger right in his face. "Don't you dare say, 'But what about George Eliot?' Don't you dare! Mary Ann Evans made her choice and so did I!'") I wasn't sure what the narrative gained by the chapter-by-chapter shifting among years, from 1944 to 1936 to 1939. I also didn't understand why sections from Nancy's husband Henri are dropped in (with a rag-right margin instead of justified), as I felt they didn't add materially to the story. Still, it's an engrossing page-turner, and I recommend it.

Opening lines: "I have gone by many names. Some of them are real--I was given four at birth alone--but most are carefully constructed personas to get me through checkpoints and across borders. They are lies scribbled on forged travel documents. Typed neatly in government files. Splashed across wanted posters. My identity is an ever-shifting thing that adapts to the need at hand."